A tax system that claims to be green is quietly punishing drivers for preserving perfectly usable older cars – and the contradictions are impossible to ignore.

There is something deeply, almost comically broken about a system that tells you to consume less, waste less, and think about the planet, while simultaneously financially penalising you for keeping a perfectly usable car on the road. Yet that is precisely where the UK finds itself today. If you own an older car, a modern classic, or even a relatively ordinary early-2000s performance saloon, you may now be paying more in Vehicle Excise Duty (VED) than someone who has just driven out of a showroom in a brand-new supercar costing six figures. That isn’t hyperbole. It’s arithmetic. And it exposes the sheer lack of joined-up thinking in modern motoring policy.

When road tax stopped making sense

VED, or road tax as most people still call it, was once a relatively blunt instrument. It existed, it was paid, and most motorists shrugged and moved on. Over time, however, it has morphed into a complex web of emissions bands, cut-off dates, exemptions, surcharges, and inconsistencies that now actively distort behaviour rather than sensibly guide it.

The most glaring problem lies with cars registered in the early to mid-2000s. Vehicles from roughly 2001 to 2006, particularly higher-performance petrol cars, often fall into the highest VED bands, with annual tax bills nudging £700–£800. These are not rare hypercars or exotic toys. They are BMW 3 Series, Mercedes saloons, Jaguars, hot hatches, and coupes that many enthusiasts saved for years to own. And yet, under today’s system, these cars are treated as environmental pariahs.

Meanwhile, newer vehicles registered after the 2017 changes often sit on a flat-rate VED, regardless of their performance or price. Add in the so-called luxury car supplement for vehicles over £40,000 and you still find scenarios where a modern supercar costs less per year to tax than a twenty-year-old performance car. That should make anyone pause.

The modern classic squeeze

This isn’t just an enthusiast gripe. It’s becoming a structural problem. Cars from the late 1990s and early 2000s are now entering what many would reasonably call modern classic territory. They represent the last era of largely analogue motoring: hydraulic steering, manual gearboxes, naturally aspirated engines, and a mechanical honesty that modern cars, for all their brilliance, simply do not replicate.

Ironically, these are also the cars that younger drivers are increasingly drawn to. Not out of nostalgia, but as a reaction. Modern cars are faster, safer, and more efficient, but they are also increasingly intrusive. Cameras watch drivers. Touchscreens dominate cabins. Software dictates behaviour. Cars are permanently connected, permanently monitored, and permanently updating. For some, that is progress. For others, it feels like ownership without autonomy. So people look backwards, not because they are anti-technology, but because they want to drive again.

VED policy, however, actively discourages this choice. By loading heavy annual costs onto older cars, it nudges owners toward scrappage or replacement. And that is where the environmental argument quietly collapses.

The environmental contradiction nobody wants to address

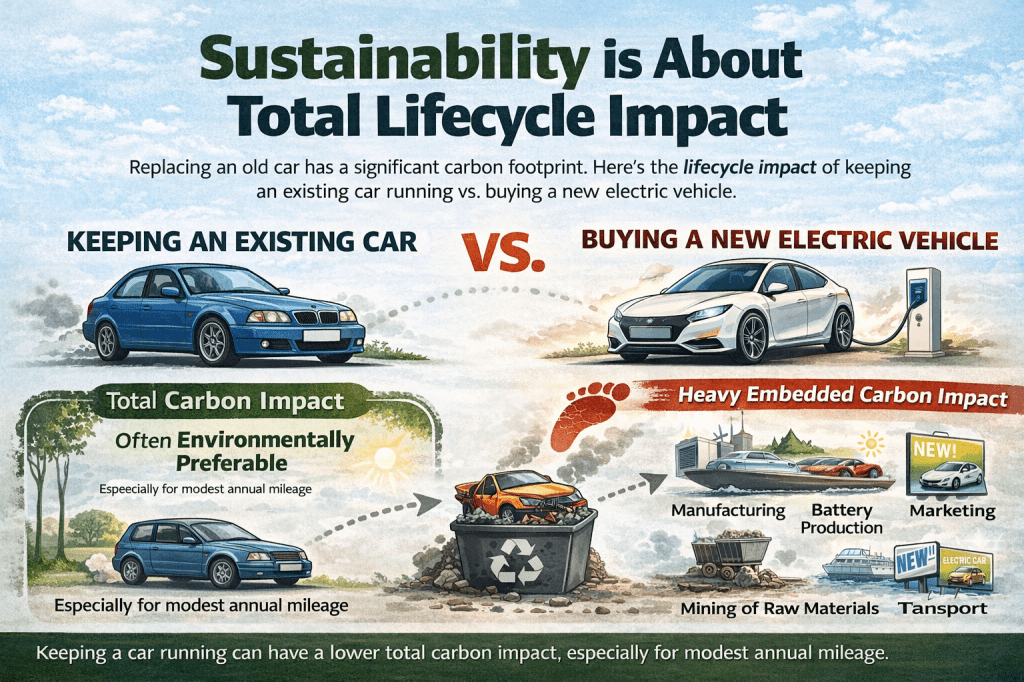

We are repeatedly told that the future of motoring must be greener, cleaner, and more sustainable. Few would seriously argue against that goal. But sustainability is not simply about tailpipe emissions measured in isolation. It is about total lifecycle impact.

Every time an old car is taken off the road, it must be replaced. That replacement car does not materialise out of thin air. It has to be manufactured, transported, marketed, and eventually disposed of. Each stage carries a carbon cost.

Electric vehicles, for all their local emissions benefits, come with a particularly heavy embedded carbon footprint, largely due to battery production and raw material extraction. That footprint can take years to offset, depending on usage patterns and energy sources.

Keeping an existing car running, especially one that covers modest annual mileage, can often be environmentally preferable to scrapping it prematurely and buying new. This is particularly true of cars built from the early 2000s onwards, when emissions standards had already improved dramatically compared with earlier decades. Yet current tax policy ignores this nuance entirely. It treats age as guilt.

Shorter lifespans, higher waste

There is another uncomfortable truth lurking beneath the surface. Modern cars, despite their sophistication, often have shorter economic lifespans. Not because engines or batteries fail overnight, but because technology moves faster than durability. Sensors, cameras, headlights, and integrated systems are expensive to repair and easy to write off. Insurance companies increasingly declare vehicles uneconomical after relatively minor impacts.

In effect, cars are becoming more like smartphones. Perfectly functional, but obsolete by design. Older cars, by contrast, are often simpler, more repairable, and more likely to be kept alive by owners who value them. Penalising these owners through taxation actively accelerates waste. If sustainability genuinely matters, that should worry policymakers.

This isn’t about politics

It’s worth stating clearly that this issue transcends party politics. The current situation is the result of policies layered on top of one another over many years, across different governments, driven by targets rather than outcomes. Blaming one colour of rosette misses the point entirely.

What is missing is joined-up thinking. A coherent motoring strategy would recognise that encouraging longer vehicle lifespans, sensible use, and fair taxation can coexist with environmental goals. Instead, we have a system that punishes behaviour we claim to support, while quietly rewarding constant consumption.

The war on the motorist, quietly continuing

For many drivers, this feels like yet another chapter in the long-running erosion of motoring freedom. Rising fuel costs, congestion charges, low-emission zones, insurance hikes, parking restrictions, and now punitive VED on older cars all add up to the same message: driving is tolerated, not valued.

And yet, for millions of people across the UK, the car is not a luxury. It is independence. It is access to work, family, community, and opportunity. Treating motorists as a problem to be managed rather than citizens to be supported is a dangerous path.

A better way forward

There is nothing radical about asking for fairness. A sensible reform of VED would acknowledge real-world usage, lifecycle impact, and proportionality. It would recognise that a cherished older car driven occasionally is not the environmental villain it is made out to be. And it would stop punishing people for choosing to maintain and preserve what they already own.

Until that happens, the contradiction remains glaring. We are told to keep things longer, waste less, and think sustainably. Then we are taxed into doing the opposite. And that, more than anything, is why the UK is punishing drivers for keeping old cars alive.

If you found this useful, interesting or fun, consider supporting me via Patreon, Ko-Fi, or even grabbing a copy of one of my books on Amazon. Every bit helps me keep creating independent automotive content that actually helps people.

Support independent car journalism 🙏🏽☺️ grab my books on Amazon, take up membership to BrownCarGuy on YouTube, or join me on Ko-Fi or Patreon.

👉🏽 Channel membership: https://www.youtube.com/browncarguy/join

👉🏽 Buy me a Coffee! https://ko-fi.com/browncarguy

👉🏽 Patreon – https://www.patreon.com/BrownCarGuy

MY BOOKS ON AMAZON!

📖 Want to become an automotive journalist, content creator, or car influencer? Check out my book: How to be an Automotive Content Creator 👉🏽 https://amzn.eu/d/7VTs0ii

📖 Quantum Races – A collection of my best automotive sci-fi short stories! 👉🏽 https://amzn.eu/d/0Y93s9g

📖 The ULEZ Files – Debut novel – all-action thriller! 👉🏽 https://amzn.eu/d/d1GXZkO

Discover more from Brown Car Guy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a comment